Three Things for Spring ☘️☘️☘️ - No. 198

Theodora FitzGibbon + Irish Yeasted Fruit Loaf + the Secret of Starch Water

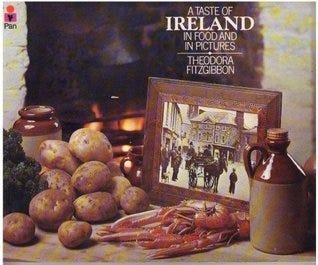

WHEN MY MOTHER WALKED INTO a Dublin bookstore decades ago and bought a book called A Taste of Ireland in Food and Pictures (1968) by Theodora FitzGibbon, who knew such a simple cookbook would bring so many pleasurable recipes to our family table?

Flipping back through this splattered and stained book today, it splays flat at Yeasted Fruit Loaf, with a big red check in the top corner of page 24. Underneath the recipe title is a small description, what cookbook writers and editors call the ‘’hednote.’’ Hers is brief but to the point:

‘’Traditional; known in Ireland as Fruit Pan.

Ireland is famous for the excellence and variety of her home-made breads. Every farmhouse and many city dwellers regularly make Irish Soda Bread, and for special occasions, yeast loaves.’’

Sadly, my mother never made Theodora’s Trout Baked in Wine with the half bottle of white wine, stick of butter, lemon and parsley poured over it on page 53, or the crispy Potato Cakes on page 27, which you wash down with whiskey and water.

But that Yeasted Fruit Loaf would begin our March baking madness. Studded with raisins, fragrant from the yeast, and rich from mashed potatoes, it was bliss. And it contained an odd cup of potato cooking water, too.

Starch water, so in vogue right now for watering your plants or just helping your pasta sauce coat each strand, has been the ultimate waste-not in Italy and definitely in Ireland where this poor country couldn’t afford to pour out a thing.

Who was Theodora FitzGibbon?

She was born Joan Eileen Rosling in London in October 1916, the daughter of John Archibald Rosling and Alice Winfred Hodgins. Her Irish father was in the Royal Navy, and a distant parent who was home little, but she traveled with him to India, Europe, and the Middle East. Educated in Belgian convents, she learned to cook at a finishing school in Paris but found more pleasure acting in repertory theater and modeling couture clothes. She was tall, blonde, and willowy and changed her name to Theodora.

In her memoir, A Taste of Love, comprised of two books written in her twenties, she shares stories of a comfortably shabby life—her lovers, her meals—and name-drops famous acquaintances as easily as a child spills crumbs from a sugar cookie. In her lifetime she was friends with poet Dylan Thomas and frequented the same parties as artists Dali and Picasso. And while it’s easy to get swept up in the celebrity and try as you might, you won’t be able to keep track of the drinks she’s had in a day, the real gems in this book are her first-hand accounts of cobbling meals together in Paris before World War II and learning a new normal during the London Blitz.

“Despite all the horrors, the Blitz was not entirely destructive, for it produced a marked change in the attitude of British people to one another. Experiencing a common danger made for a friendliness, almost a love, amongst total strangers. People were concerned with helping their neighbours: there was a joke or a laugh to keep their spirits up, and a sharing of scarce commodities. The last pinch of tea, or a bottle of whisky, was offered by people one had never seen before and might never see again.”

— A Taste of Love. Theodora FitzGibbon.

After a messy divorce, Theodora moved to Ireland, and would write 25 cookbooks, the most masterful of which was The Food of the Western World (1976), an encyclopedic feat covering 34 countries and taking 15 years to pull together.

She would become the first president of the Irish Food Writers’ Guild. According to the Belfast Telegraph, people devotedly read and cooked her recipes because they wanted to live her life.

In my mother’s tattered copy of A Taste of Ireland, Theodora is a careful guardian of Irish cuisine, respectful of simple people and places where this food, her food, was constructed, giving historical context and simple, straightforward recipes. The book is filled with 19th Century black and white photos belonging to her second husband, the Irish filmmaker George Morrison. And she writes in the introduction:

‘’We, in Ireland, have long memories: the aromas from the kitchens of our childhood remain when many other things are forgotten. I hope that this little book will revive those memories and bring pleasure to all who use it.’’

Theodora FitzGibbon died in March 1991 in Killiney, Ireland. She was 74. I don’t think my mother could have made a better choice in a cookbook that day. And I am positive the tour bus was double-parked outside waiting on her to make a decision so they could roll on to the next town.

Why something as simple as potato water helps us bake better bread

Andrew Janjigian writes Wordloaf here on Substack and is everything bread—doctor, guru, therapist, engineer all rolled up in one. For 11 years he was test cook, editor and ‘’resident breadhead’’ at Cook’s Illustrated magazine. Today, in addition to writing his fascinating and lively Substack, he writes and develops recipes for Serious Eats, King Arthur, and Epicurious.

So I knew Andrew was who I needed to call regarding starch water in bread.

My Yeasted Fruit Loaf always baked up rich and fragrant with sufficient moisture to help it last a few days on the kitchen counter if we hadn’t devoured it in one sitting. I suspected it was the starchy water from cooking the potatoes and the mashed potatoes themselves. And if it was, then could I use this tactic in other recipes?

Andrew said yes.

We’re talking not so much about starch water, he said, as the gel that forms to keep a network of starches on the inside of the bread. It’s the same principle as when you add cornstarch to thicken a sauce. The liquid goes from loose to silky and glossy.

‘’The water gets bound up and trapped,’’ Andrew said, ‘’like stealth water, it’s hidden because it is gelled. It makes the bread softer and moister and means it is slower to stale.’’

We also talked about another trick I’ve been using lately when making yeast rolls from a soft and sticky dough.